You dream of creating services, programs, and spaces that respond to your community. And you know that you need to plan ahead in order to accomplish that while making the best use of your limited time and budget. The possibilities for service seem endless, but your resources aren’t. How do you make meaningful plans—the kind that don’t just sit on a shelf, but actually guide your day-to-day work and result in a deeply engaged community?

My favorite method for creating highly relevant, inclusive strategies is community-led planning (CLP). CLP works whether you’re creating something as large as an organization-wide strategic plan, as permanent as a physical building, or as small and ephemeral as a single program. It’s a way of creating plans with, rather than simply for, your community. And it can unleash your library’s creativity in ways you never dreamed.

What Is Community-Led Planning, and Why Would I Use It?

Community-led planning describes a process where the community holds as much power as the library—or ideally, more power—to make decisions. The community decides what the goals of the plan or program should be, what metrics of success are meaningful, and what actions will help us get there. The library stays fully engaged, providing support and resources, and co-creating the services, spaces, or programs that result. (For more on this, check out the IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation, or Hart’s Ladder, or one of the many other community engagement models.)

This approach is a tangible way of acting on our core values of equity, diversity, inclusion, and justice. CLP pushes us to take an asset-based perspective. In libraries, we are often trained to focus on deficits—to see our communities (especially BIPOC and marginalized communities) as holes of need that we, as helpers and even saviors, can fill. CLP rejects this paradigm. Instead, it sees our community as rich with strengths, brilliance, and dreams. CLP centers our community’s desires, its goals, and its approaches for reaching them. The library embraces cultural humility when we recognize that our community doesn’t need us to come up with the answers—it already has them. We must understand that it is a privilege for the library to be allowed to participate in them.

CLP also has some important additional benefits. When you use CLP, you know, beyond any doubt, that what you are producing is meaningful to your community. Why? Because the community made it for themselves. And chances are good that what they make will look quite different from what the library would have created on its own, leading to all kinds of creative new services. And those innovative new services have a built-in audience. The partners involved will show up and bring their networks along. And your time and resources will go further, because each partner in the plan has something to contribute.

Okay, I’m Convinced! How Do I Use Community-Led Planning?

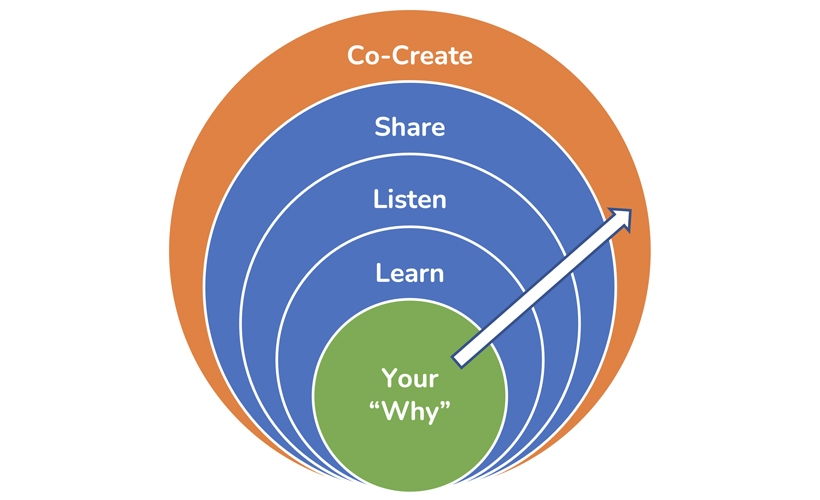

The basic outline of the method I use with my clients looks like this. It’s intentionally broad because you can use a lot of different methods at each stage, depending on what you’re trying to plan.

- Your “Why.” Why are you making this plan in the first place? What are your core values and vision? You’ll need to know this up front so that you can be respectful of the partners you engage, making good use of their time, asking meaningful questions, and being prepared to take real action alongside them.

- Learn. Do your homework. You’re going to start engaging directly with folks in your community, in particular those impacted by systemic oppression and bias. It’s not up to them to educate you. So you need to get a lay of the land first. What can you learn about the community you are hoping to reach? What is the broader social and environmental context for the topic you’re looking to tackle? Infobase offers some great tools and databases that can help you research.

- Listen. Start talking to people directly! This is the heart of the whole method. You need real humans involved in the messy business of creating the future together. This can be formal interviews or focus groups, or just a cup of coffee and a chat. Do not ask about the library in your first conversation. Ask about them—their goals and dreams and passions, the work that excites them, and the barriers they face.

- Share. After you’ve talked with a lot of different folks, you’ll have noticed some recurring areas of alignment between their “why” and yours. Go back to them and tell them what you heard. Don’t skip this step—it’s essential for building trust.

- Co-create. Now the real fun begins. In your sharing conversation, invite people back to co-design the response with you. You have found some big ideas—now what, exactly, do they look like in practice? Make programs. Design spaces. Write strategic plans. Design thinking and participatory design techniques are your friend here. (Check out this toolkit from IDEO to get started.) Creation is iterative; everything doesn’t have to be perfect the first time. So all along the way, reflect on how you’re relating to and empowering others, and keep trying to do better.

Want more specifics?

There are some fabulous toolkits out there to take you through this step by step, or to provide a deeper dive into using specific techniques like asset mapping or semi-structured interviewing. I’m particularly partial to the Working Together Project’s Community-Led Libraries Toolkit. There’s also some really useful content from ALA and the Harwood Institute, the Aspen Institute, and the University of Kansas Community Tool Box.

Sounds Great, but I’m Not Sure My Library Is Ready for This….

That’s OK! Everyone comes to this work with a different level of readiness. My research interest is how we increase a library’s capacity—what we can change or improve to make it easier to adopt this important approach. One simple tip is to always tie your justification for using CLP to your library’s guiding documents—your vision, mission, strategic plans, annual goals, or whatever it is that speaks to your leadership and colleagues. The more you can demonstrate how this work helps the organization advance its mission, the more likely folks will be to make time and space for it.

For more on the twelve research-based factors that can help your library increase capacity for community-led planning, look for my book, tentatively titled Twelve Steps to a Community-Led Library, coming out later this year.

See also: